Interviewed by Lily Kuenzler for The Word Factory

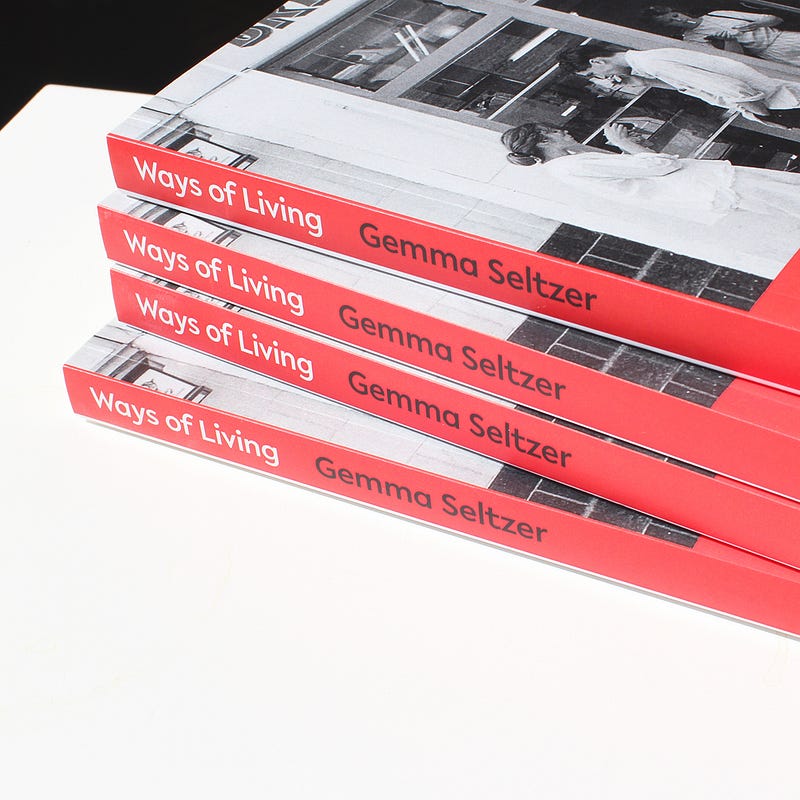

I interviewed Gemma Seltzer ahead of her anticipated short story collection Ways of Living, releasing on the 15th July. This idiosyncratic and thoughtful collection is one not to miss. Centred around women’s experiences on the streets of London, Gemma explains to me how the paths she has walked led her to this collection.

A self-proclaimed ‘gentle person’, I spoke to Gemma’s about the collaborative nature of writing, the fragmented realities of the pandemic and the peace and quiet of the mornings.

Q: Congratulations on the release of your collection ‘Ways of Living’ this July. Can you talk about the collection and what inspired you?

A: Ways of Living is about women and the ways they live in and navigate the city. There’s 10 stories containing bold women who do extraordinary and strange things on London streets. All the pieces have been drafted while walking in the city. That’s part of my process. I walk and absorb information. The stories contain overheard conversations and memories and pieces of the landscape. I’m interested in what it’s like to be in London as a woman. The joy of London and also the reality of it — the small spaces and the frustration and the expense. Then the outrage that we often hold within our bodies when we’re experiencing harassment or the exhaustion of constantly anticipating harassment. The stories reflect the choices women make as they move through the city: where they go and don’t go. How women’s friendships are played out on the streets. One of the women walks with her arms held out like chicken wings, when she’s bashing her way through crowds. Another one hides in a cupboard after a stressful commute in the rain. These are kind of funny, but they’re also the reality of women’s experiences.

Q: You say walking is part of your process. Can you describe your typical walk to me?

A: I am interested in how we exist outdoors as women. Lots of my stories take place outdoors, or in hotels or cafes or on the pavements or parks. And that reflects where I like to walk. In lockdown, like so many people, I ended up practicing the same route over and over again. I became interested in these small routes and how mundane things become familiar. I wondered what happens to us as we keep treading the same path. I live in Southeast London, and there’s a nice pocket of parks around me. There is something joyful that I find in the rhythm of walking and how it settles my thoughts. I start to absorb and see different things. There’s a Virginia Woolf quote from her essay ‘Street Haunting’, which is about walking through London. She talks about how the body merges with your surroundings once you leave home and you become: “a central oyster of perceptiveness, an enormous eye”. It’s the same with writing: you get into that flow, sometimes you lose a sense of your body entirely. There is something compelling about becoming an eye, an observer, being invisible in the city, looking out, disappearing, merging with the streets. And anyway, identity is a slippery thing: one day you’re one person and another day you’re someone else.

Q: All of the stories are told from female perspectives. Why did you make that decision?

A: I feel there is a gap in literature and culture where the primary relationship depicted is female friendship. Often women’s relationships are there in relation to men: being wives or mothers or lovers or daughters. The reality of female friendship is that it’s intense and passionate and brilliant and heartbreaking. But I don’t think we as a society have a vocabulary for it. I definitely found that when I was writing the book. That’s why in my work there’s often quiet and things unsaid. It’s hard to describe your feelings about friends. What we’re doing is artists and writers is trying to express our version of the world to other people. But there is a gap in my vocabulary and other people’s work. We lack a language to describe deep, intense and meaningful female friendship. We end up borrowing language from romantic relationships, or other kinds of relationships like parent-child ones.

Q: Can you talk to me about the role of quiet and what is not said in your work?

A: There’s lots of moments in the book where there are misunderstandings or something is whispered, which we don’t hear as readers. There’s a power in quiet. I’m sensitive to sound, my natural state is quiet — I’m a gentle person. I can happily not speak all day. But I’m interested in how to translate not talking into stories; there is plenty of dialogue and chat in my work but there’s also quiet. Moments where people don’t follow up in the way you expect them to. I want to explore how women talk and don’t talk alongside each other.

Q: How has the pandemic influenced your creative practice?

A: Everything has felt fragmented and strange. It’s been tough, like it has been for a lot of people. During the first lockdown I left my job. I signed the contract for this book. I started doing a lot more events online. I was unable to see a lot of people that I cared about. I did write though. For example, the collection’s final story Parched is set during lockdown, with masks and anti-bacterial spray. I wrote that during the first lockdown in that weird, intense period where everything was taking place on Zoom, and our private lives suddenly became public: what you had in your background, these intimate spaces were on display. Then you went out onto the streets, and there was nobody there. It was like these two had swapped over. I had a sense that real life was taking place on screen. And the streets outside were dangerous or mysterious in some way. The story opens with a woman crying on Zoom. She ends up being recruited for a collective of professional criers. I set that story in the room I was sitting in. I was looking at my screen on Zoom, and looking out the window, which I was describing in the story. The real world and the fictional world felt like they’d switched places. In answer I was able to write, but it became quite intense. Experiences became narrow. The stimulus I was having was just the four walls of my room. There’s an intensity to that story that I fear and hope captures something of that experience of the pandemic.

Q: Can you tell me about your ‘Write and Shine’ morning writers group, which used to take place in sites across London but since the pandemic has been taking place over Zoom?

A: Write and Shine is a program of morning writing events. I set it up in 2015. It began taking place in peaceful London venues. Then the pandemic hit and I moved it all on to Zoom, which is working out really well. We’ve been able to grow and now we’ve got a community all over the UK and Europe. It’s one of the joys of technology that we can bring people together. We run in seasons, as life is constantly moving and shifting around us we use that as creative inspiration. We look out our windows, and make sure we are noticing how the trees are coming into bloom. Still trying to connect with what’s happening outside in our lives, but doing that through technology. That’s been powerful.

Q: Do you find in your own practice that you prefer to write in the mornings?

I do. I’ve always been an early riser. I like to write as the light arrives. I have a morning routine where I do Julia Cameron’s morning pages. Then I meditate and spend time looking out the window with a cup of tea, just being in the quiet. That’s important to me: I need to not talk. In the mornings as soon as I start talking, I forget my thoughts and I forget what I wanted to write. Even if I’ve got an early morning workshop, I get up a bit earlier. I naturally have it in my body to wake up early anyway. There’s research that says we are more creative in the morning because we’re on the edge of sleep and more sensitive to the different sights and sounds in our environment. I’ve definitely found it’s the best time to imagine and start writing before the to do list rises up and the inner critic rears its head. I allow minimum 15 minutes, hopefully more like half an hour/an hour, just be in the morning and write and think and get ready for the day.

Q: Almost all of your work is set in London. Did you grow up there? And what does the city mean to you personally now?

A: I do love London. I find a never ending well of stories here. I was born in North London, in Edgware. But I grew up in Luton, north of London. After Luton I lived in a few places and traveled and then returned in 2006. I haven’t left since. I just love it. I get so much energy from being here. It’s such a living, breathing city. I’ve thought a lot about London during the pandemic — the first time I went back into Central London I was like a flower being watered: I could feel the energy rising up in my body. I once had a residency that was in a lookout tower on an isolated beach and I couldn’t write. I was looking out the window, seeing if anyone was going to walk past and nobody did. There’s a quote on my desk, which is by an academic called Gerda Wekerle: “A woman’s place is in the city.” I love that. Because the places we live in are made by men, and they’re full of big phallic skyscrapers. And the names and statues are all of men designed with men’s needs in mind. But cities are shaped by women. Women come to cities for the jobs and they take up space in public and economic spheres. Cities offer infrastructure for women to help manage their lives and responsibilities, from takeaway restaurants to transport and childcare. And we as women, particularly women writers, can enjoy that amazing mix of community and anonymity in the city that can free us from society’s and other people’s expectations. There’s still a long way to go, though. Given the very real concerns about women’s safety, the idea of a woman’s place being in the city feels like an aspiration. But it’s also an important invitation for us to do the work imagining this new kind of city.

Q: From VR projects to photo-diaries, variety seems to fuel much of your creativity. Can you talk to me about some of the different projects you have done and how they invigorate your creative practice?

I wrote the script for a VR piece about a bird in Hawaii, now extinct. It was a collaborative project, which excited me and made me question what it is to be to be a writer. You have to be open to shifting and changing. You never say your work is finished if you’re writing a script, because somebody else will take a part of it, and continue the idea. I’ve also done improvised projects with dancers, providing text in response to their movement. That dancer would take some of the text and use it as a choreographic tool. And I would respond again. So there is fluidity. For those projects, I had to form a different relationship with my words. They weren’t wholly mine anymore. Something shared and new was created.

Q: Here at Word Factory we are all about the short story. Do you have any advice for our budding writers?

I love Word Factory and the work you’re doing. Thanks again for having me today. I say: trust that the path you’re on will lead you where you need to go. And read more than you write. Read to remind yourself of the joy of a well chosen word and a beautiful image. Read to escape for a while and then return with a renewed energy to the page.